Last week, Bloomberg published an article criticizing luxury goods maker LVMH for unpaid labor in its supply chain that allowed the company to sell a $9,000 vicuña sweater. I made a short video (Tik Tok | Immunohistochemistry) My original takeaway about it is that I found the article’s approach “a little slimy.” I get frustrated when the media attacks a company’s success. There are many examples of bad behavior that merit such an attack, but success should not be one of them. Sometimes the attack misses the target entirely.

A common example is when a reporter reports that a consumer products company (i.e., the company that makes and sells commonly purchased cereals) is making “record profits,” while consumers in the supermarket aisles are being hit by higher prices. blow. In most cases, these profits are reported on a dollar basis rather than as a percentage of revenue. But if profits fall on the latter basis, then “record” profits don’t necessarily mean the company is healthy. Since companies use profits to fund their operations and working capital, if profit margins (profit as a proportion of revenue) decline, eventually the company will need to rely on external sources of capital such as debt, which will cost money and further reduce profits, which may trigger Vicious Cycle (Related Article: Working Capital vs. Cash Flow).

Returning to the Bloomberg article, before making my aforementioned “somewhat mushy” comment, I edited the conclusion and instead wrote that the article “ignored a lot of variables.” (Note: I find it boring, too.) I can’t confirm whether this article is the product of lazy journalism, or laziness by design.

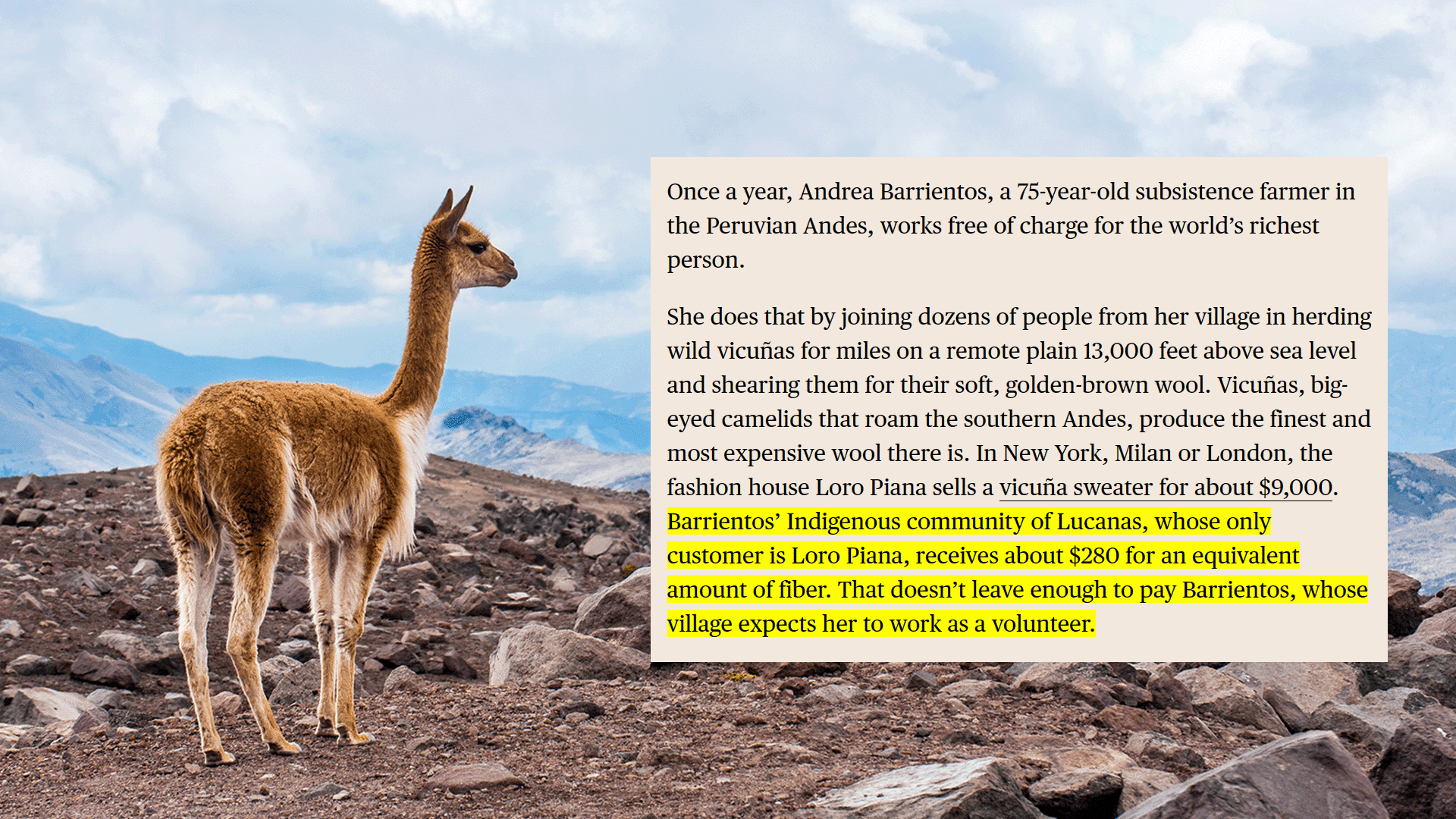

The article begins with a misleading claim, “Once a year, Andrea Barrientos, a 75-year-old subsistence farmer in the Peruvian Andes, works for the world’s richest man for free.” They were, of course, referring to Bernard Arnault, the founder and chief executive of LVMH. What a way to get your readers excited. The conclusion of the next paragraph states that asking the farmer to volunteer because her village cannot afford to pay her… isn’t quite right. So let’s explore what’s going on. But first, let’s learn about this soft, lovable animal, the camel, whose wool is so popular.

(Image source: Bloomberg – association)

What is camel hair

I would never have guessed this, but vicuña is the smallest living member of the camel family, and (I would have guessed) the wild cousin of the more well-known and domesticated alpaca. Native to the Andes Mountains of South America, camels were becoming something of a tragedy of the commons before they were granted legal protection in 1969. The global camel population has dropped to around 6,000. Since there is no incentive to protect these animals and no one has property rights in these animals, hunters simply kill and skin these animals for their very valuable wool.

At only 12 microns (1/12,000 mm) in diameter, camel hair is one of the finest natural fibers in the world. Products made from it are extremely soft and an animal can only produce about 0.5 kilograms or 1.1 pounds of wool at most. As far as I know, it takes three years for the animal to regrow its fur.

Since conservation measures were implemented, the vicuña population has recovered to about 350,000 animals today. The legal market for wool, which can be sheared from the animals without harming them, provides poor communities in the vicuña’s habitat the opportunity to profit from the natural resource.

So why aren’t farmers in the Lucanas community getting paid?

Why does this happen?

The same Bloomberg article also links to a study explaining this: Local communities in Peru and their elected president negotiate wool prices with Loro Piana and decide how to allocate the revenue they receive from the company (see bottom for more details) ). Loro Piana did not ask whether the shearers were paid.I can’t confirm this, but if I had to guess, I’d assume that community chairs do get paid (according to study“Management is directed by managers and all employees are paid.”).

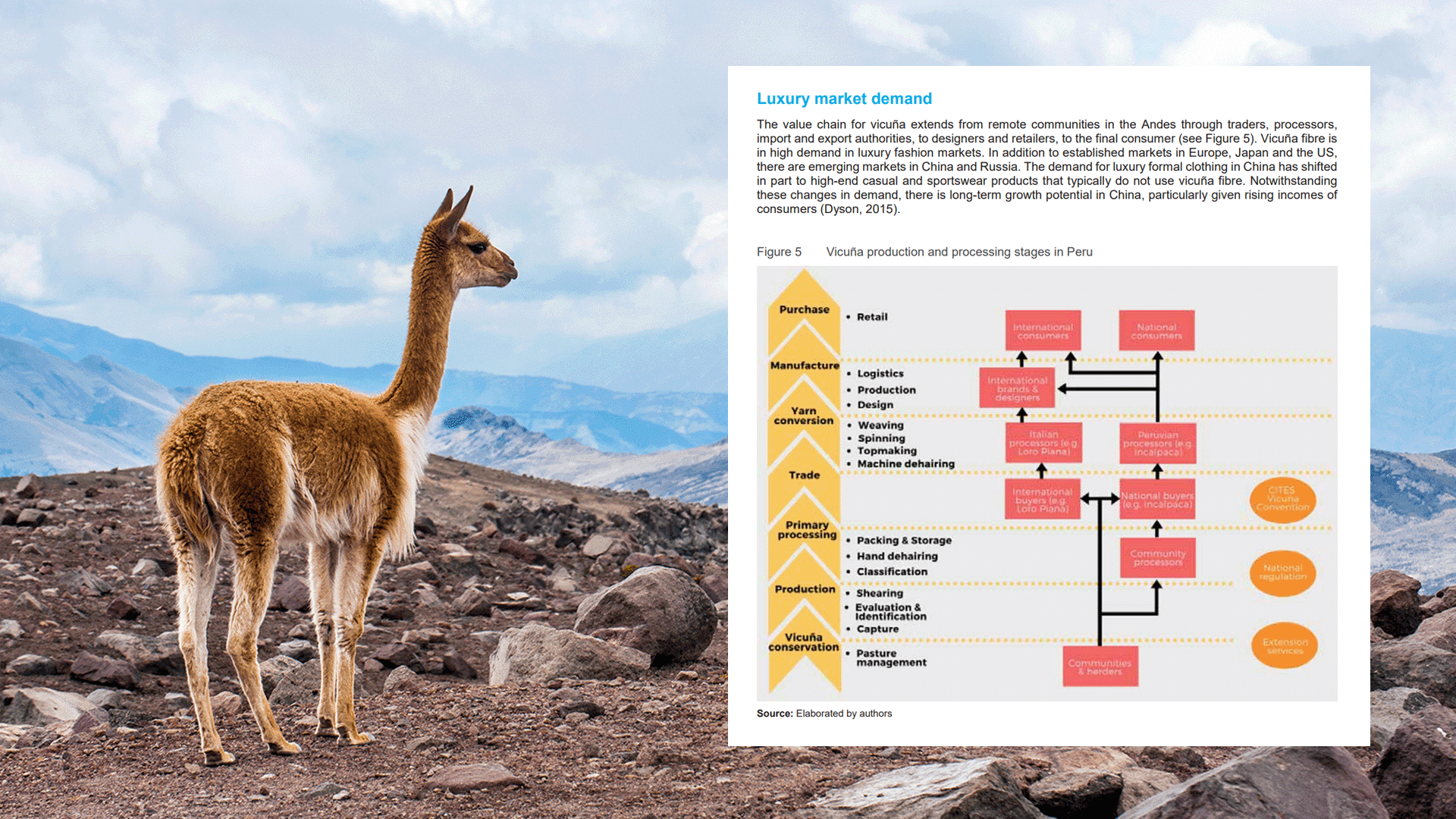

The second thing this article ignores is that raw materials (other than precious metals, diamonds, and gemstones) typically only account for a small portion of the sales price of most luxury goods.

Raw material costs

Likewise, shearing vicuña hair is only a small part of the process of producing a finished product from wool. For example, spinning tiny fibers into high-quality yarn requires expensive machinery and complex expertise, and communities like Lucanas have so far lacked the resources to climb the supply chain and reap greater returns by adding value to their raw materials .

Interestingly, the greatest value added throughout the supply chain occurs in the final stages, when a product like a sweater becomes more ethereal—a brand—and skillful marketing leads consumers to believe it is worth more than the sum of its products. part. This dynamic isn’t unique to camel hair sweaters.

Rolex manufacturing costs

As I explored in a past article (What Makes a Rolex So Expensive?), the raw material costs of a Rolex watch are almost negligible compared to the price at which they are sold. For example, the Rolex Cosmograph Daytona in stainless steel costs less than $1 and sells for about $13,000. Even a white gold version of the same watch, with a price tag of $41,000, only contains about $8,000 of the precious metal. (Note: These prices are from an article in 2020. Before the pandemic caused watch prices to skyrocket.)

Birkin bag manufacturing cost

The same goes for the Birkin bag, which, despite being handmade, only costs around $800 to produce, according to The Economist . This is a basic bag that can cost as low as five figures. Is a $50,000 Birkin bag made of crocodile skin? It costs approximately $1,000 to $1,500, which is only 2% to 3% of the purchase price. The most exclusive versions of this Hermès product can sell for hundreds of thousands of dollars. This is the power of brand.

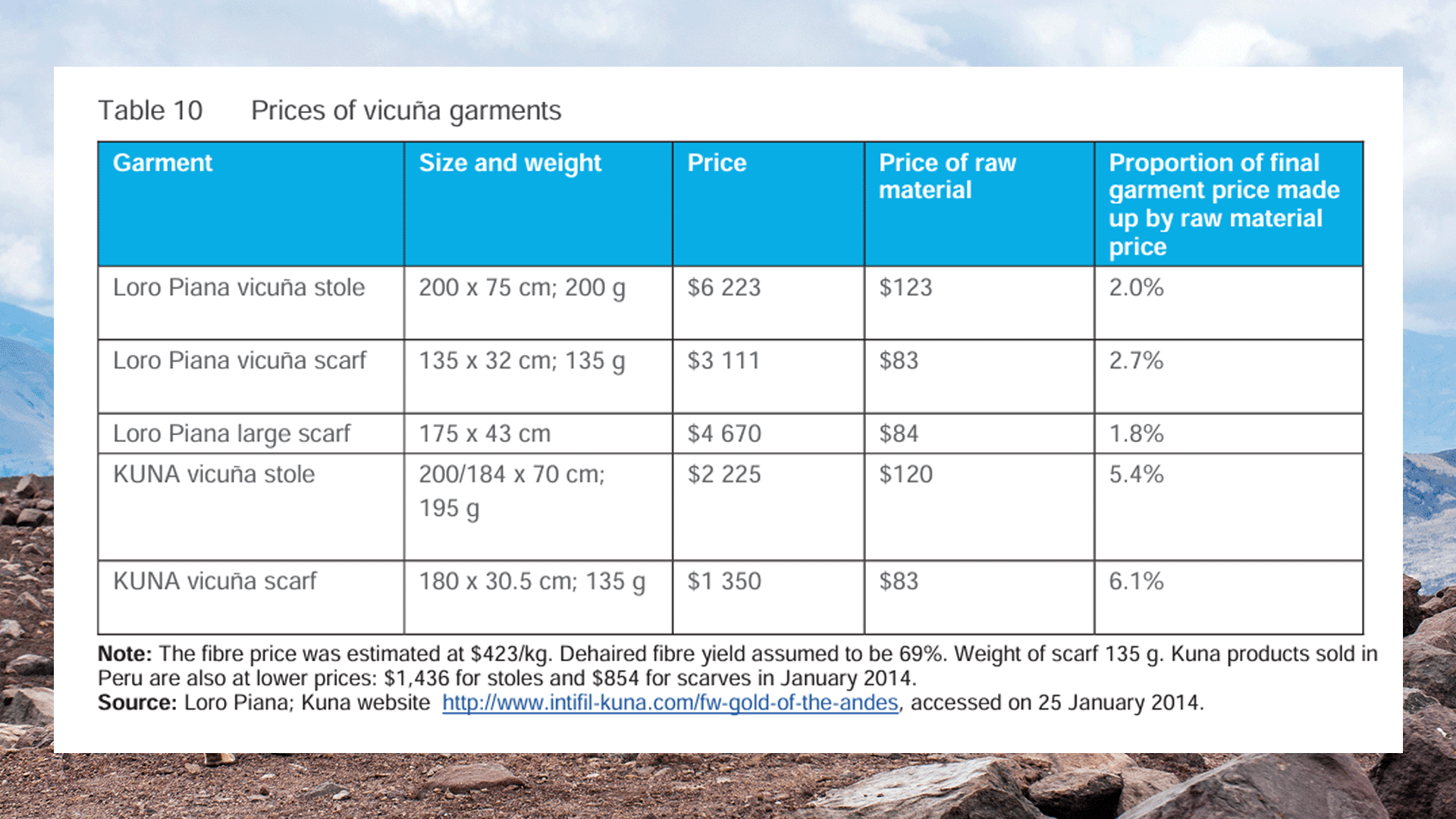

Raw material cost of Vicuña sweater

Like Rolex and Birkin bags, the raw materials of Loro Piana’s vicuña hair products only account for about 2-3% of the sales price, as shown in the table below. Even for lesser-known brands like Kuna, camel hair only accounts for about 5-6% of the final product price.

(Image source: Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora – association)

brand value

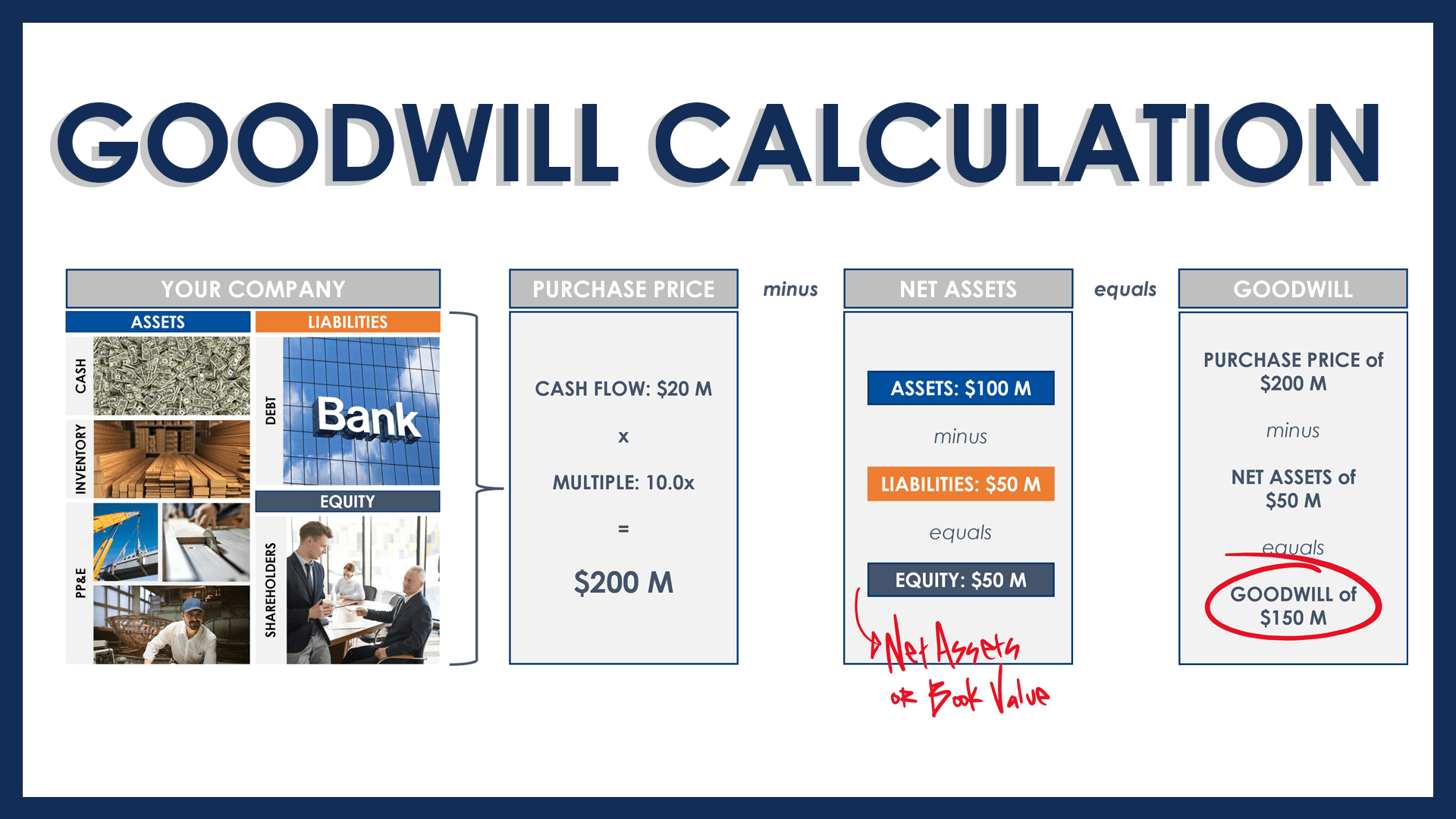

If you buy one of these luxury goods companies, first you need a dump truck full of cash, and second, after the deal closes, you have to allocate a substantial amount of the purchase price to goodwill (see post on Goodwill). This is because a large part of the value lies not in a company’s physical resources, but in a brand like Loro Piana (founded in 1924) that has been built over decades, or Hermes (founded in 1837) in recent years. The intangible value of a century-old brand.

Why aren’t farmers getting paid?

That’s fair enough, but 2-3% of $9,000 for a Loro Piana sweater is clearly greater than zero. So why isn’t Andrea Barrientos getting paid for her work? Her village, Lucanas, operates as a communal economy but is still very much rooted in tradition. Elected village leaders negotiate the price of camel hair with Loro Piana. The article stated that approximately $280 is enough to make a sweater, “which is not enough to cover Barrientos’ expenses.” This is controversial, but regardless, the leaders of Lucanas have decreed that villagers must shear sheep for free. The leadership then spends the proceeds on things that might help the entire village.

Like anything else, the income from vicuña hair has definitely brought some changes in the lives of ordinary villagers. The article stated that the local poverty rate exceeded 80% in 1969 and dropped to 41% in 2018. Still high, but a significant improvement in a generation.

A lack of educational resources is clearly part of the problem. According to the article, Barrientos even mistakenly believed she was prohibited from wearing clothing made of camel hair. While this was true in Inca times, when only royalty could wear camel hair, that’s no longer the case, although Barrientos would certainly have had a hard time affording a Loro Piana sweater, especially when she had her sheep sheared for free.

What is oligopoly

Can I pay more for Loro Piana? Are the current prices reasonable? It’s a small market that’s easily influenced, so it’s hard to define fairness. It operates in an oligopoly fashion, a market that may have many sellers but only a few buyers. Loro Piana buys most of the world’s vicuña hair (because their brand can market it well). Therefore, in this environment, sellers are not always able to confidently exercise their negotiating power (how experts negotiate: video | text).

in conclusion

In my opinion, the Bloomberg article wanted to tell a story of exploitation, subtly blaming Loro Piana for poverty in rural Andes. But the story isn’t that simple, and I’m usually a fan of “simplicity.”

Before demonizing the company, it’s important to remember that Loro Piana has raised awareness and demand for camel wool, which is attracting resources to impoverished areas. Few companies operate at the scale to go through the tedious and expensive process of converting raw materials into refined products and successfully sell the finished products into highly competitive markets with confidence. Sustaining the luxury brands that support this effort requires significant investment (tiffany video). This is why many people who try to do this lose wealth.

That said, I’m not here to support LVMH more broadly. I have no idea what a fair price for vicuña hair is, or how much the community should pay to have this fiber delivered. This will require more research. But if a sensational claim can be debunked with a few quick internet searches, then I have to say, it’s a little slimy.