loyalty

Welcome to another installment of our weekly CEF market review, where we discuss more of the closed-end fund (“CEF”) market activity from the bottom up (focusing on individual fund news and events) as well as the top down (providing an overview) Vast market.We also try to provide Some historical background and relevant themes that appear to be driving the market or that investors should be aware of.

This update covers the period during the last week of March. Be sure to check out our other weekly updates covering the business development companies (“BDCs”) and preferred stock/baby bond markets for a broader perspective on the income space.

market action

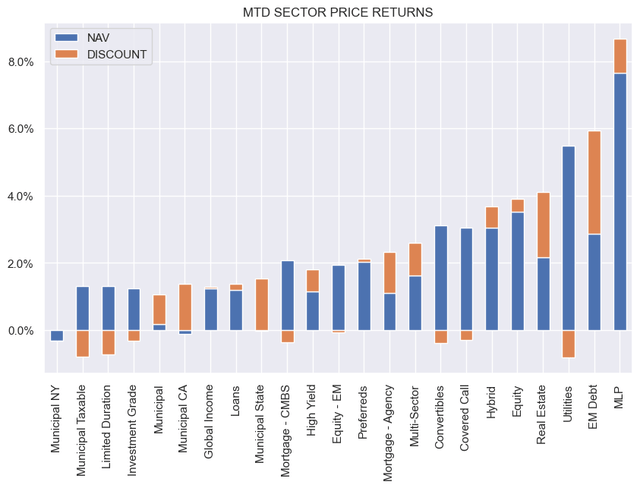

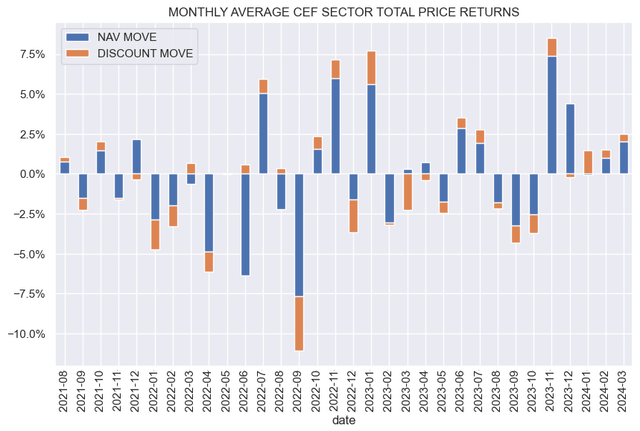

Most CEF sectors are up again this week. All but one sector posted profits in March, led by emerging market debt and MLPs Way.

systematic income

It was the fifth consecutive month of gains, with March the sector’s best return so far this year.

systematic income

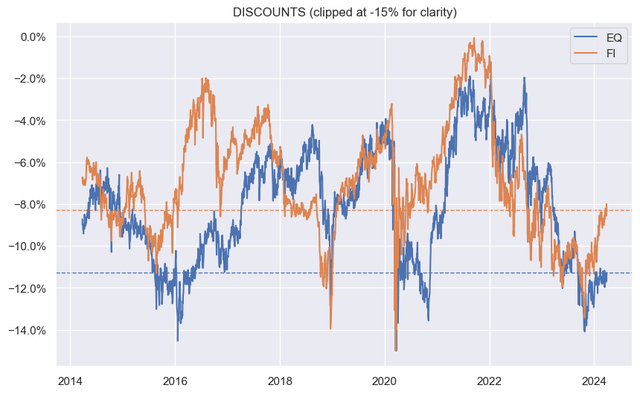

While fixed income CEF industry discounts have tightened to near historical averages, equity CEF industry discounts remain significant.

systematic income

market theme

One of the factors that sometimes disappoints investors with CEF investing is the less than ideal long-term net worth trajectory of many funds. We look at this dynamic within the context of the preferred CEF industry over the past few years.

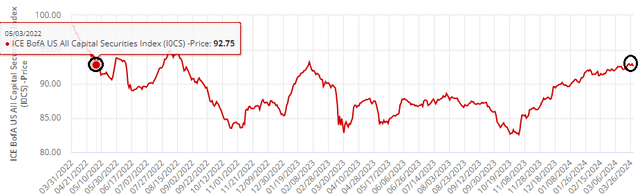

We start with a broad-based preferred stock index—the ICE BofA All-U.S. Capital Securities Index. For simplicity, we identify periods in which the index price is unchanged. One of the periods is from May 3, 2022 to March 28, 2024, as shown below.

ice

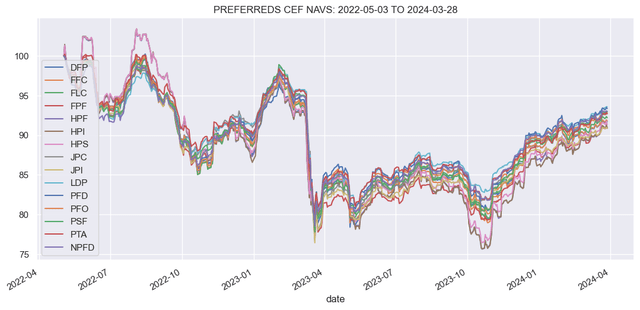

Now looking at the normalized (i.e. starting at $100) preferred CEF NAV over the same period, we find that, unlike the index’s fixed price, all fund NAV had negative returns ranging from -6% to -9%.

systematic income

Why are the indexes flat while all CEF sector NAVs are down?

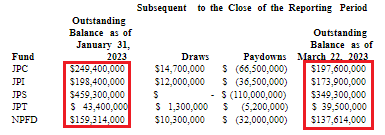

There may be several reasons. One is deleveraging. When asset prices fall, CEF leverage increases. This makes it more difficult for a fund to maintain its leverage levels, especially if the fund has a leverage cap. For example, we see that between January and March 22, 2023 (when bank preferred stocks declined sharply), Nuveen preferred CEFs gave up on bank borrowings. While deleveraging does not guarantee a permanent loss of NAV, it often does so because funds tend to wait to repurchase assets when prices rise above sale levels (which reduces the fund’s leverage, creating more multiple assets). room for additional assets). This “sell low, buy high” strategy is a drag on net worth.

Nouwen

In a flat index environment, a second reason for NAV declines may be the divergence between the fund’s portfolio and the broader index. Obviously, even if it were possible, each fund would not replicate the index – fund managers have their own views and objectives. However, this does mean that fund performance tends to deviate from the index.

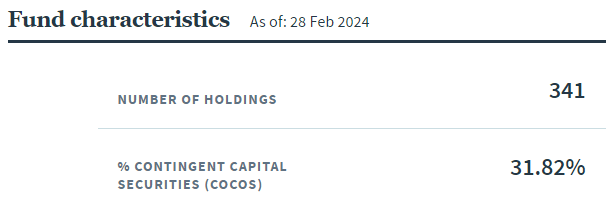

For example, preferred CEFs were, and still are, overweight contingent convertible securities. After Credit Suisse collapsed, Swiss regulators wrote down CS CoCos to zero, leaving the securities in trouble. CoCo and AT1 securities make up less than 20% of the broader market, but many preferred CEFs hold far more securities than they have in their portfolios, which caused some pain last year. That’s not to say it’s a bad decision in the long run, but it may have something to do with the deleveraging mechanism mentioned above.

Nouwen

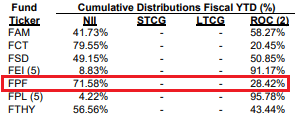

A third reason might be overallocation. Most credit funds tend to have distributions in excess of their net income levels, as do many preferred persistence funds. This isn’t a big deal from a total return perspective, but it does mean the NAV could fall more than expected.

first trust

The fourth reason is trading slippage. The index is based on medium-term asset values and ignores any turnover costs that may increase over the longer term. Hopefully the alpha generated by managers will cover this cost, but this is not always the case.

Ultimately, there are a number of mechanisms that could adversely affect a credit fund’s NAV relative to its underlying benchmark. This doesn’t mean investors should avoid CEFs. However, it does mean that investors need to take the time to identify sectors that are likely to experience benchmark underperformance, as well as funds within that sector that are capable of outperformance for a variety of structural reasons.

Market comments

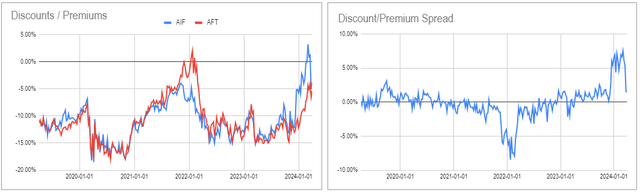

In particular, Apollo Lending’s two CEFs and AIFs have underperformed over the past week. Until the reversal occurred in the last two days of this week, the AIF discount expanded by 10% and the AFT discount expanded by 5%.

It’s unclear what the catalyst for AIF’s collapse was – it began ahead of a recent SEC filing that once again described the mechanics of a merger with MFIC, if approved. If AIF returned to its recent peak premium of 3.3% (for example, a price of $15.37 and an NAV of $14.87), AIF investors would receive 0.965 MFIC shares for each AIF share, equivalent to a value of $14.18. Thereafter, each AIF share will receive an additional payment of $0.25 as an incentive for voting in favor, for a total of $14.43. In other words, AIF shareholders priced 1 share of AIF at $15.37 and ended up with $14.43, which doesn’t seem like an amazing deal.

Now that AIF has opened up the discount, the math makes more sense. In fact, if the AIF discount widens further to 10%, then there might even be around 5-6% value for owning the fund and voting in favor of the merger.

Another consequence of the recent volatility in AIF and AFT is that the unusual valuation divergence we highlighted earlier is essentially over.

Systematic Income CEF Tool