Courtnick

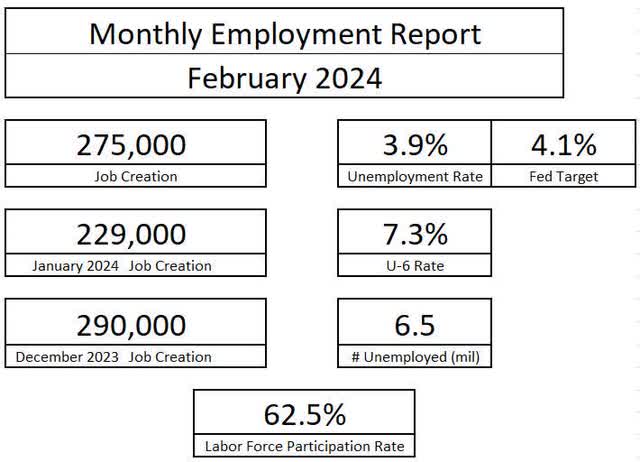

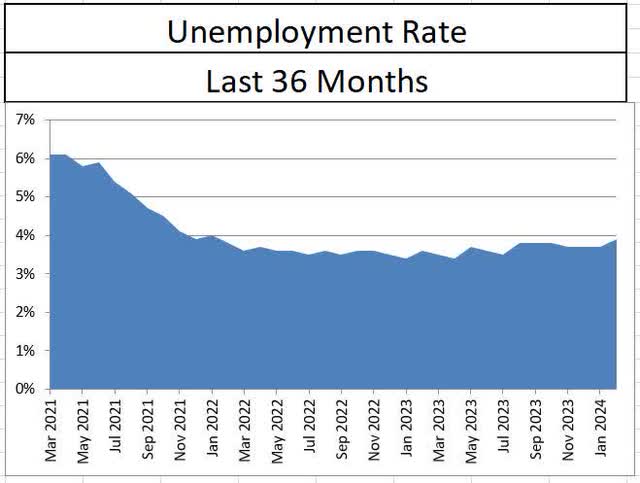

Earlier today, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics released February nonfarm payrolls report. The report showed that the economy created 275,000 jobs in February, stronger than expected, but the unemployment rate rose to 3.9%.part The strong jobs report was offset by a downward revision of a combined 167,000 jobs reported in December and January. At present, the labor market is continuing to normalize, but it shows no signs of requiring the Federal Reserve to cut interest rates.

Bureau of Labor Statistics Bureau of Labor Statistics

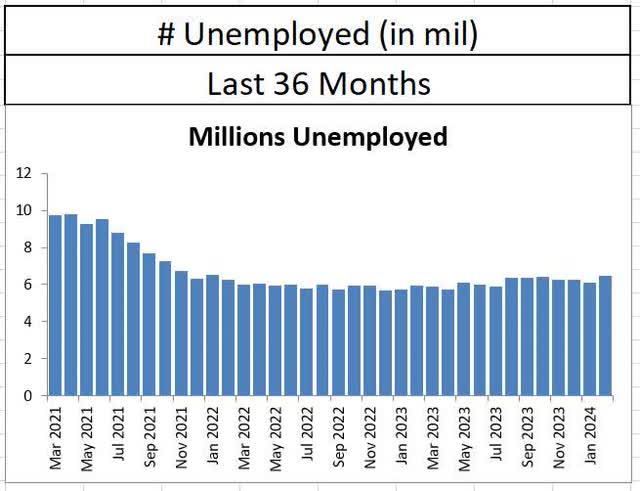

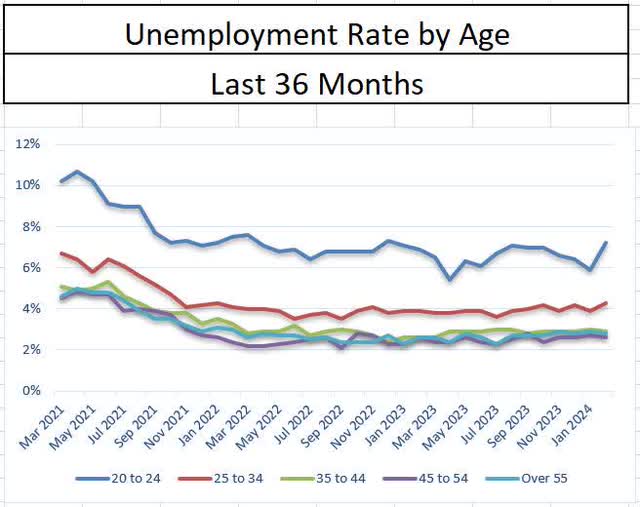

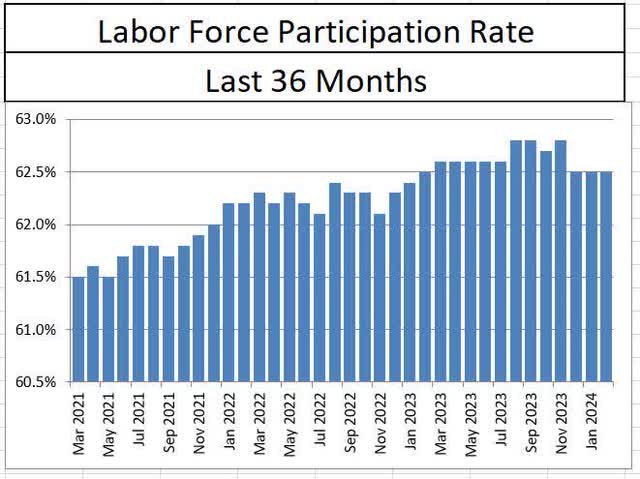

The unemployment rate jumped to 3.9% in February, the highest level since January 2022. As the economy creates jobs, the unemployment rate also rises, indicating that the labor force is growing faster than employment. Created. Those who enter (or re-enter) The labor force is immediately counted as unemployed. The number of unemployed people increased by 340,000 in February to 6.46 million.

Bureau of Labor Statistics Bureau of Labor Statistics

Looking at the February jobs report, it was clear that the increase in unemployment was caused by new entrants into the labor force. This is best illustrated by the surge in unemployment among those aged 20 to 24 in February. Although the unemployment rate among those aged 25 to 34 also increased, the magnitude was not as significant. The unemployment rate among workers over 35 years old remained stable.

Bureau of Labor Statistics

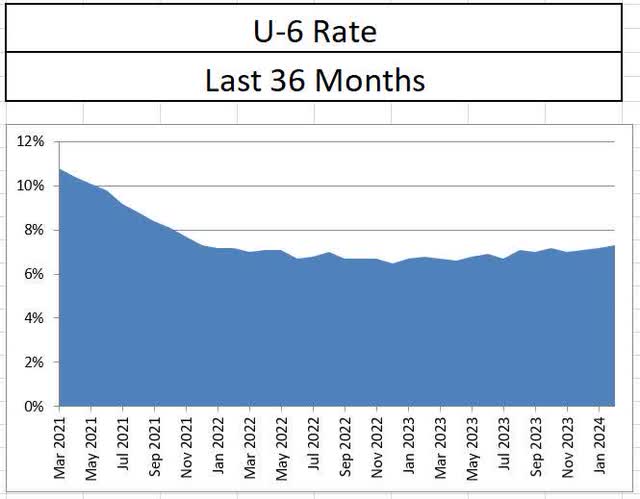

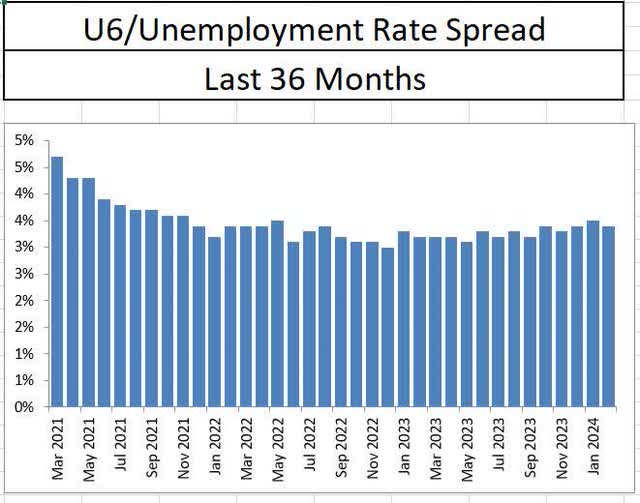

In addition to the surge in young workers joining the workforce, there are other signs that things are normalizing. The U6 rate, which includes marginalized or underutilized workers, has also continued to rise and is now at its highest level since December 2021. The U6U3 rate, which specifically measures the number of marginalized workers, did fall by a tenth in February, but remains at the high end of the two-year range.

Bureau of Labor Statistics Bureau of Labor Statistics

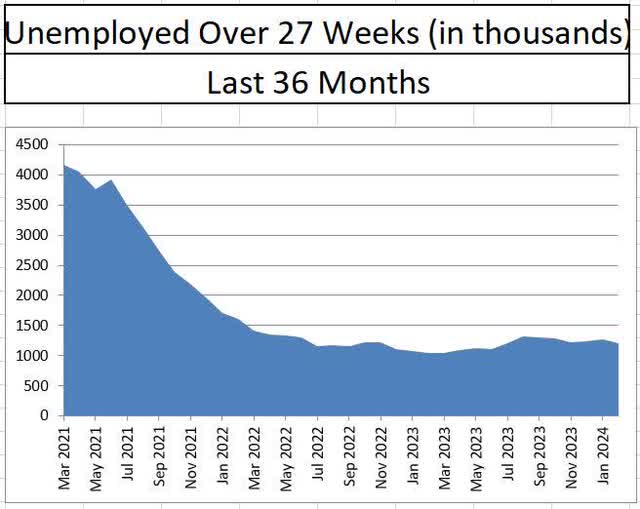

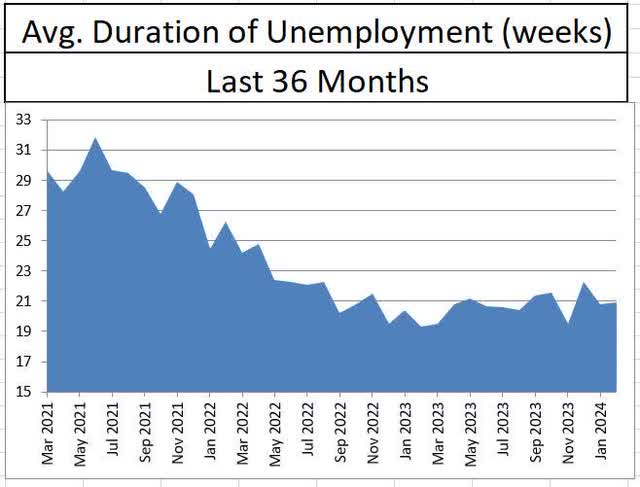

Despite normalizing indicators, several data points in the report point to continued restrictive pressures on the labor market. The total number of workers unemployed for more than 27 weeks fell to 1.203 million in February, the lowest level since June 2023. This suggests an ongoing pattern of shorter unemployment durations, leading to the belief that a large number of newly unemployed workers one month could lead to larger job growth numbers in subsequent months.

Bureau of Labor Statistics Bureau of Labor Statistics

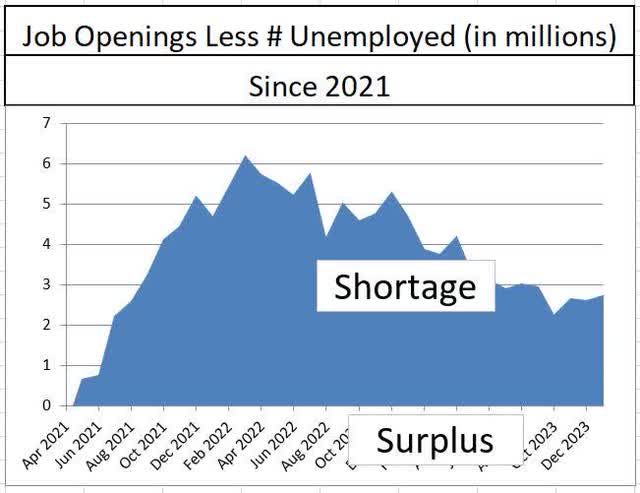

Another indicator that supports the relationship between increases in unemployment and subsequent job creation is the number of job openings. The report, done separately by the Bureau of Labor Statistics, comes a month after the labor report but still provides insight. As of the end of January, due to the impact of the epidemic, the number of employed people has decreased and the number of unemployed people has eased, but the shortage of labor supply still exists.

Bureau of Labor Statistics

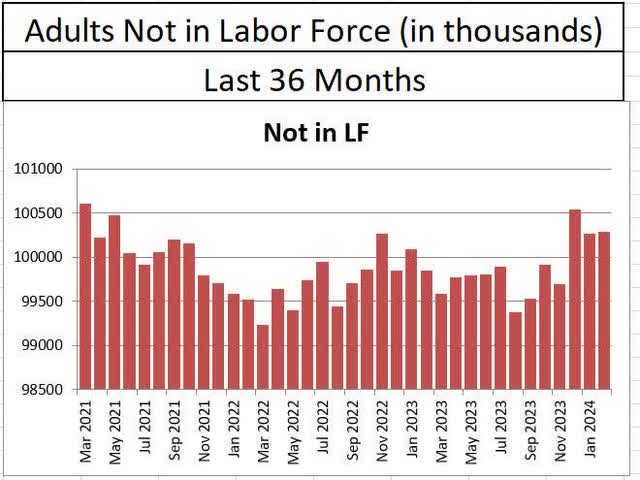

In addition to shorter unemployment durations, we are still seeing pressure on labor supply. Although stable in February, more than 500,000 adults have dropped out of the labor market since November. Growth in adults not in the labor force has also weighed on the labor force participation rate, which has not risen since November.

Bureau of Labor Statistics Bureau of Labor Statistics

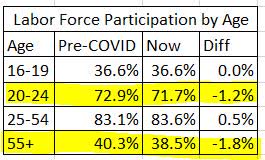

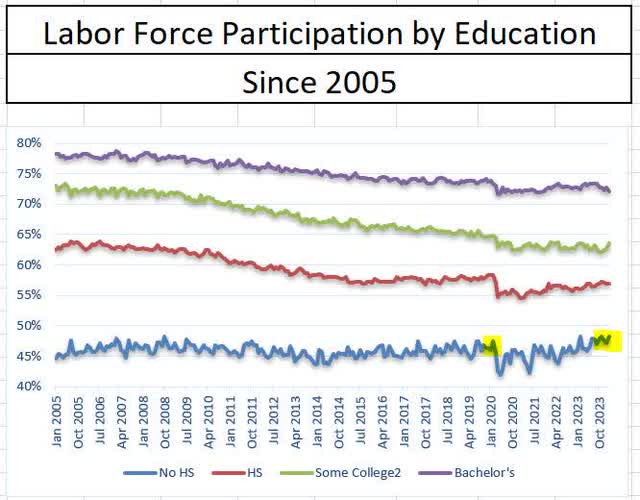

Over the next few months, more adults may enter the workforce, but they may not be between the ages of 25 and 54. The labor force participation rate for this group continues to be higher than pre-pandemic levels. Currently, participation rates are lower among workers aged 20 to 24 and those aged 55 and over. It’s also important to note that labor force participation rates among uneducated workers are higher than before the pandemic. The labor force needs more educated workers to re-enter to relieve supply pressure.

Bureau of Labor Statistics Bureau of Labor Statistics

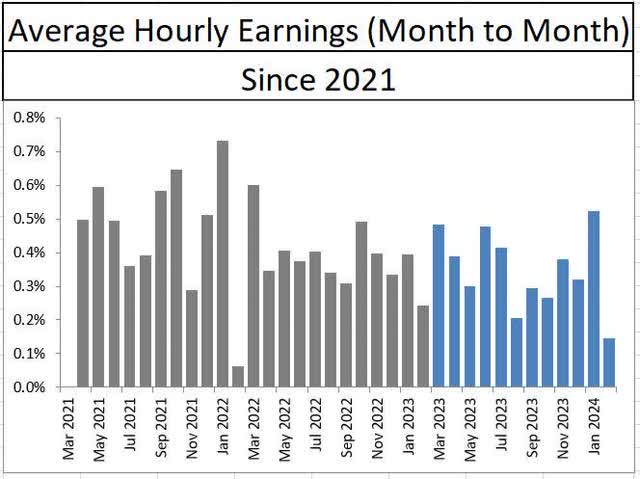

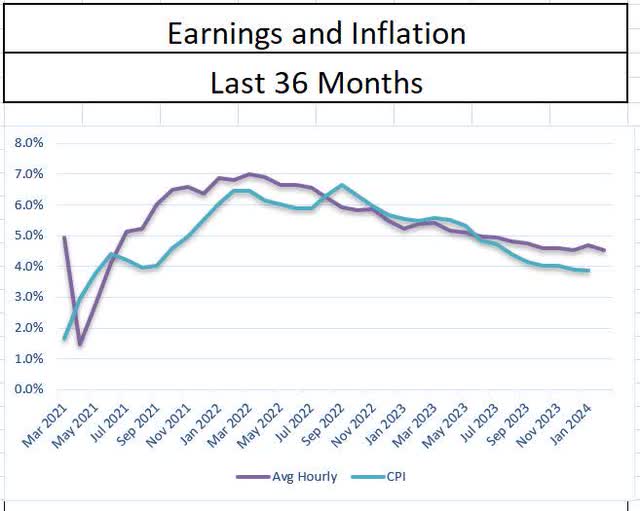

As the tug-of-war between softening and tightening in the monthly jobs report continues, one encouraging piece of news from the Federal Reserve for February came in the form of wage data. Average hourly earnings increased by 0.1% in February, the slowest growth rate in two years. Slower wage growth should continue to help deflation continue, as consumers with less wage growth tend to spend less.

Bureau of Labor Statistics Bureau of Labor Statistics

Overall, I don’t think the Fed saw anything actionable from the February jobs report. While wage growth is encouraging, we need to see data beyond next week’s CPI report. If the Fed decides to cut interest rates, which appears to be a near-term possibility, wage growth could pick up and put immediate upward pressure on prices. For now, I think the Fed should delay action until the data shows real economic weakness.