Douglas Rising

The Senate on Friday passed a $460 billion spending bill to keep the U.S. government running, eliminating the possibility of multiple agency closures for the remainder of the fiscal year. “Kathy Stech Ferek, wall street magazine.

“Friday’s measure authorizes funding for federal agencies through the end of the current fiscal year at the end of September. Negotiators are still wrangling the terms of the remaining six bills, which have a March 22 deadline before any additional funding for those bills is reached. Agencies provide funding and it becomes ineffective.”

“Unfinished bills are considered more difficult to complete because they are difficult charging issues…”

As a result, Congress once again shelved the first set of bills and is expected to do the same with the second set of bills.

Still the same, still the same…

But what about budget?

What about debt?

Well, it looks like this game will go on forever.

However, things did change. Budgeting practices have changed.

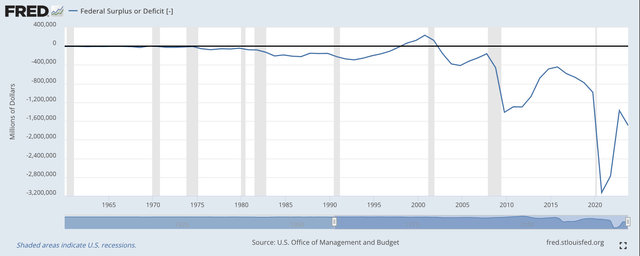

Look at America’s budget history.

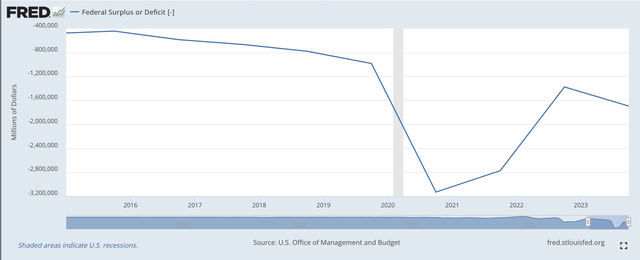

federal deficit or surplus (U.S. Federal Reserve)

Things have changed.

But let’s look at it from the Clinton administration’s budget surplus period.

These surpluses ended under the Bush II administration in the early twentieth century. However, the size of the following deficits is generally small.

I want to draw your attention to the differences that occurred in the 2010s during the Obama administration.

The increase in budget deficits that occurred at this time can be interpreted as a change in overall policy priorities that persists to this day.

During this period, Ben Bernanke introduced his new policy ideas into the Obama administration, particularly in policymaking at the Federal Reserve.

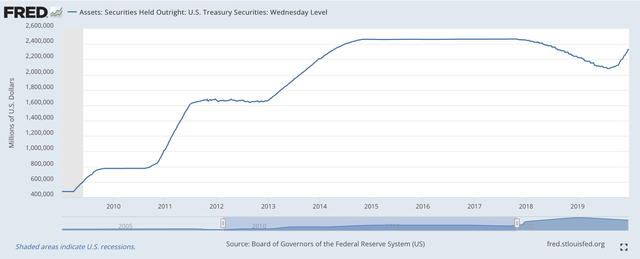

Ben Bernanke introduced the concept of quantitative easing into the policy making of the Federal Reserve. Quantitative easing means that the Fed will directly purchase securities to steadily increase its investment portfolio, without saying a word about what might happen in the federal budget.

In the chart below, you can see three rounds of quantitative easing that took place in the early 2010s.

securities held outstanding (U.S. Federal Reserve)

Ben Bernanke served as Chairman of the Federal Reserve from 2006 to 2014. He proposed the quantitative easing policy to the Federal Reserve and oversaw the first three rounds of quantitative easing policy by the Federal Reserve.

Janet Yellen followed Bernanke as Fed chair but did not launch quantitative easing during her tenure. Jerome Powell became Fed Chairman in 2018.

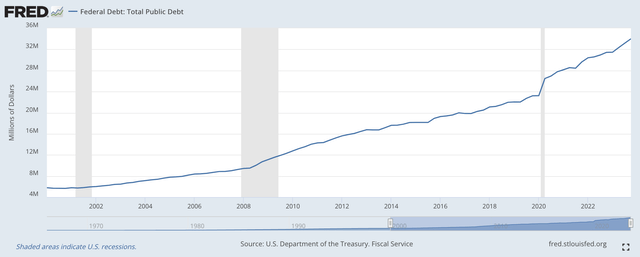

During this period, the federal government created massive debt.

total public debt (U.S. Federal Reserve)

Note that in 2008, the slope of the curve shifted upward, and this shift continued into 2019, when the curve jumped upward, and then continued at a faster rate toward the end of the period.

Bernanke’s quantitative easing program appears to be accompanied by a significant increase in government spending and debt-financed government spending.

As the Fed engages in quantitative easing and the federal government issues large amounts of new government debt, one might expect this to create an environment of sharply higher prices.

This didn’t happen.

Moderate but steady growth in the Fed’s portfolio of securities sets the framework for the path of inflation.

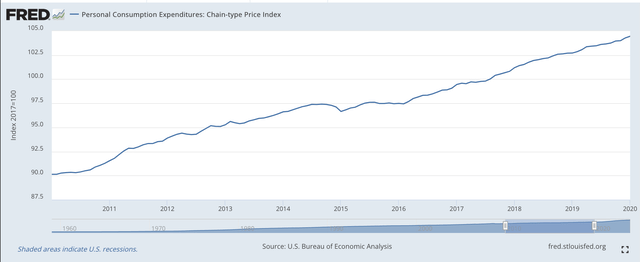

This is a photo from the 2010s.

Price increases for personal consumption expenditures (U.S. Federal Reserve)

The compound consumer price inflation rate during this period was approximately 2.3%.

good.

We have the Fed doing quantitative easing, we have unprecedented federal spending, and… price inflation is very tame.

Clearly, Bernanke’s quantitative easing program dominates.

What has happened since the Covid-19 pandemic?

federal surplus or deficit (U.S. Federal Reserve)

The federal deficit fell sharply.

And, that’s the budget situation we seem to be in the middle of right now.

Under Jerome Powell, the Fed implemented very, very broad quantitative easing to protect the economy from the downside, and then, as inflation appeared to be picking up, the Fed pivoted in March 2022 adopted the quantitative easing policy. Tighten.

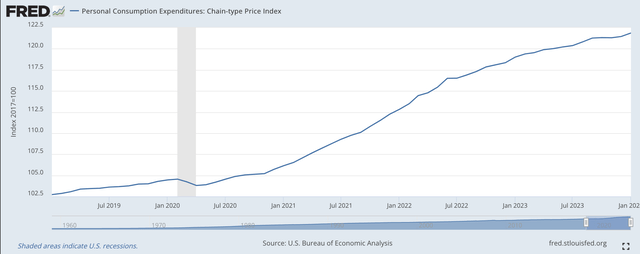

So, what role does price play?

Price increases for personal consumption expenditures (U.S. Federal Reserve)

Price inflation rose during this period, but has fallen rapidly as a result of the Fed’s quantitative tightening policy.

Currently, consumer price inflation is 3.1% and appears to be declining.

Once again we see that changes in monetary policy have the greatest impact on prices, while fiscal policy fails to directly drive the rate of change in prices.

How do we explain this?

Government deficits and growing government debt could affect how the Fed handles its portfolio of securities.

Larger and persistent government deficits create growing federal debt, potentially forcing the Fed to buy more securities to prevent interest rates from rising.

In this case, rising government deficits and debt are likely to increase upward pressure on prices. But this is only because fiscal policy “forces” monetary policy to provide more “money” to financial markets.

In Mr. Bernanke’s plan, monetary policy will not be “forced” to become increasingly loose.

The current round of quantitative tightening by the Federal Reserve has lasted for 24 months. The Fed has not stopped disposing of directly purchased securities in two years.

The Fed appears to have convinced investors to follow its lead. The federal government can “do its own thing” while prices and inflation follow the Fed’s actions.

As Nobel Prize winner Milton Friedman said, inflation is a monetary problem.

Mr. Ben Bernanke appears to have constructed a monetary policy system consistent with Mr. Friedman’s conclusions… and it works.

The federal budget and deficit are rising. Inflation appears to be falling. The well-disciplined Fed appears to be doing its job.