If you’re interested in investing, you should know about serial entrepreneur and investor Brad Jacobs. His most recent book, How to make billionsa masterclass in acquisitions, integrations and “big, hairy deals” that sometimes create net worth in the ten-figures. (Quick video introduction: association.)

Buy and build history

Jacobs started playing the entrepreneurial game early. In 1979, three years after dropping out of Brown University, he co-founded Amerex Oil Associates and served as CEO until selling the oil brokerage in 1983, which at that time had offices around the world and Annual brokerage volume reaches $4.7 billion. He continued to focus on oil trading until 1989, when he founded United Waste Systems to acquire solid waste management companies. It’s an interesting jump from the beginning of the supply chain (energy) to the end (waste disposal). In 1992, Jacobs took the company public and then Sold in 1997 for $2.5 billion. As a public company, it has outperformed the S&P 500 by more than five times over five years.

In September 1997, Jacobs founded United Rentals and began to integrate equipment rental companies across North America. It took only 13 months to build it into the world’s largest equipment rental company. According to “Fortune” magazine, during the ten years under Jacobs’ leadership, the company completed 250 acquisitions and became the 536th largest company in the United States. The company eventually became “100 times bigger,” with its stock price increasing more than 100 times from its starting price of $3.50. Today it trades at over $675.

It’s no coincidence that Jacobs named two of his early companies “United.” They are all very successful aggregation businesses, where investors buy multiple smaller companies in the same industry and combine them into a larger integrated company. Since the market generally rewards scale with higher valuations, in a sense, aggregation strategies arbitrage scale, and private equity firms or independent sponsors hope to receive a higher multiple of EBITDA on exit. Summary There are other potential benefits, such as economies of scale and cross-selling, but multiple arbitrage is one of the most powerful drivers of value, and Jacobs’ leverage is on a scale that few investors can come close to.

Jacobs’ next venture, XPO Logistics, began in 2011 with a $150 million private investment in public equity (PIPE) that gave him majority control of a transportation and logistics company called Express-1 Expedited Solutions right. Jacobs built XPO into a market leader and then split it into three different public companies (XPO, GXO and RXO).

Now, after taking time to write his book, Jacobs’ investment firm – Jacobs Private Equity LLC – of which he is a managing partner – is reportedly gearing up to join forces with a new venture QXO restructures construction products distribution.

Create shareholder value

Clearly, Jacobs crushed it through conglomeration. But while multiple arbitrage exists, you can’t simply aggregate companies at random and expect to be wildly successful. Creating value is also important. “As far as I know, the simplest way to create tremendous shareholder value is to buy businesses at profit multiples below the multiples at which our stock trades and then significantly improve those businesses,” Jacobs wrote.

Examples of value-added acquisitions

This is standard private equity summary language for public companies. How to make billions Describes a very smart way Jacobs added value to United Rentals. Shortly after founding the company, he acquired Wynne Systems, whose software is used by much of the equipment rental industry. This strategic move gives United access to anonymized data about what’s happening across the industry, allowing them to spot developing trends such as oversupply or shortages and react faster than competitors.

Scale requires large, hairy transactions

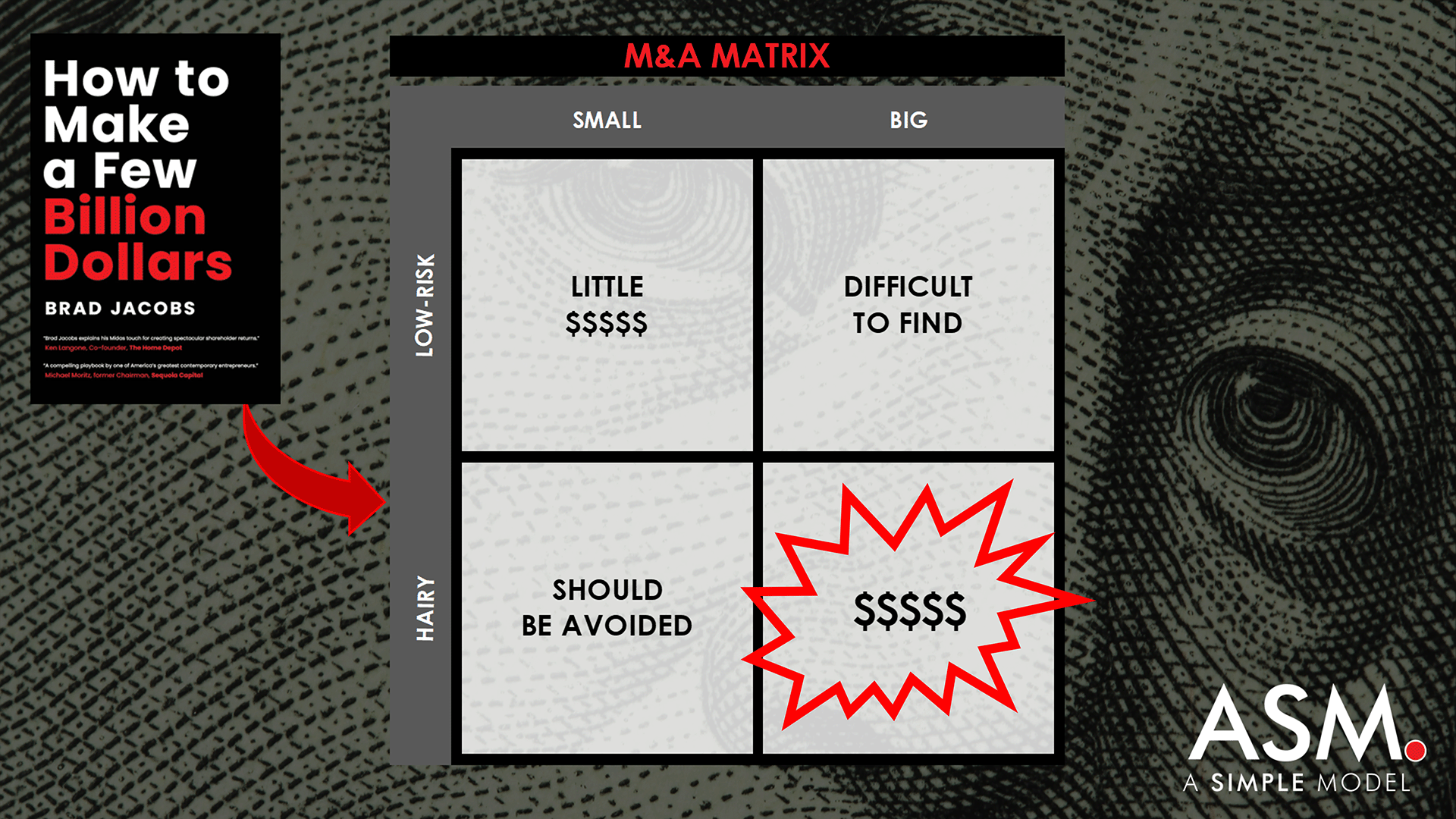

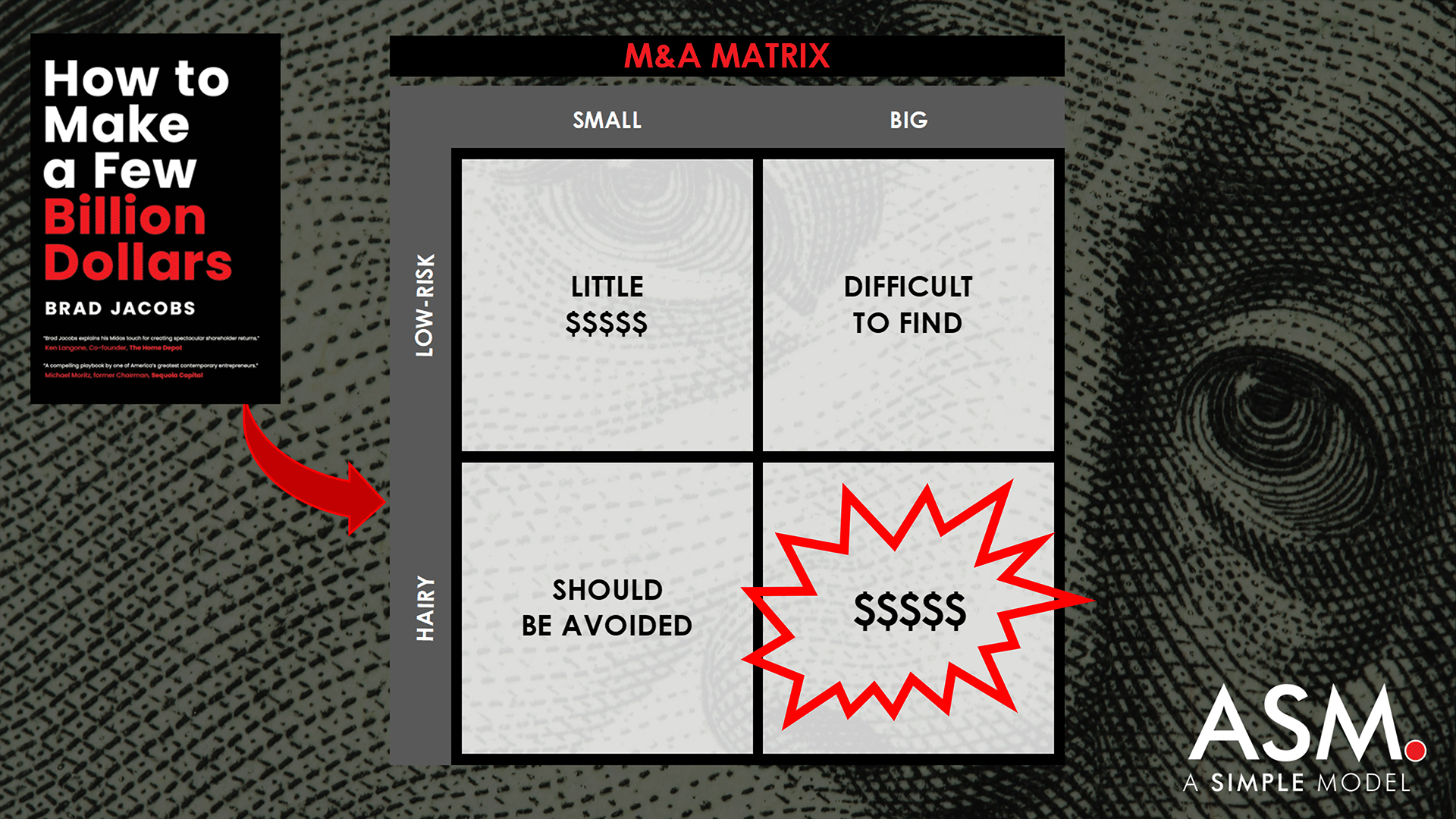

Now I’m sure you understand what Jacobs means; this guy is very, very good. He didn’t get there by playing it safe. “Large, low-risk trades are what everyone wants,” he writes, “but they don’t exist.” He illustrates this with a matrix like the one below, in which we will simply Mark large, low-risk deals as “hard to find” (never say never, right?).

This leaves three quadrants in which you can play the role of a startup investor. Jacobs believes that the Southwest Quadrant should be avoided. Small, hairy deals bring the worst of both worlds: headaches and little reward. If you want to stay small, small, low-risk trades in the Northwest Quadrant are fine. The southeast quadrant, what Jacobs calls the “Bingo” square, is where you want to be. These deals aren’t easy. But if the problem can be solved, that’s where the big money is.If you want to increase your chances of finding it, I highly recommend reading How to make billions.