Afternoon pictures

What’s old is new again

“Whenever Charlie and I buy common stock…, we treat the transaction as if it were a private business. We look at the economic prospects of the business, the people who are running it and the financial health of the business.” The price we have to pay… When investing, we think of ourselves as business analysts, not market analysts, not macroeconomic analysts, not even securities analysts. ”——Warren Buffett

This quote succinctly sums up the philosophy that makes Warren Buffett one of the greatest investors of all time. It demonstrates the first principles passed down to us over the years by Warren Buffett, Charlie Munger, and other great investors. In this overstimulated world, where speculators outnumber investors and it’s common to check one’s account every second of the day, we have lost the art and science of long-term investing.

“The basic principle that applies here is that the value of capital at any moment is derived from the value of the future income expected to be generated by that capital.” — Irving Fisher

Today, the principle of treating stocks as ownership stakes in actual businesses and valuing them in terms of what private investors are willing to pay to acquire the entire business seems to have disappeared. Likewise, the idea that investors should receive part of the profits earned by a company in the form of dividends seems to have disappeared. Now is the time to update these ideas.

To that end, Daniel Perris has written an excellent new book called Ownership Dividends . In it, he first made the case for dividends and against the current market culture that views stock buybacks as the primary capital return vehicle. He then looks back at the financial academic community and their 60-year war on dividends.

“Over the past 60-plus years, leaders in the academic finance community have been almost equally unanimous in their explicit rejection of the most straightforward “default” manifestation of the minority shareholder discounted cash flow approach to publicly traded stocks. That is, they eliminated dividends”

The real challenge for factor investors who use subjective academic work to drive their investment process is that it is only the academic work that they deem important and relevant to their particular brand of investing. There is a wealth of academic and practical research that contradicts their findings. The most notable example is probably Benjamin Graham and his famous security analysis. As Perris outlines in the book:

“…Investor and Columbia Business School professor Benjamin Graham wrote the first modern comprehensive report on stock market investing, Security Analysis. It was published in 1934. Read it. It’s all about related to dividends. Graham probably came closest to this simple assertion that the purpose of the modern corporation is to gather capital, build a scale business, generate profits, and distribute them to the owners of the corporation.”

He further elaborates on this idea by reviewing John Burr Williams’ 1938 paper “A Theory of Investment Value.” “It provides the first detailed calculation of the key mathematical principles of discounted cash flow valuation and discounted dividend models as they apply to stocks.”

In short, there is more than four centuries of practical history behind owning a business for dividends, and scholars have been doing the math and putting it into practice since at least the first half of the 20th century. Prominent business leaders of the day understood that dividends, even if not sanctioned by the academy, were an appropriate form of return for investors who provided capital. “

He believes that value investing has become too academic and challenges conventional wisdom in academia. Ultimately, Perris believes a paradigm shift is coming as the tech giants leading the market mature and may shift toward paying dividends to shareholders. We’ve seen this happen already, with Meta (META) declaring a dividend and other tech giants likely to follow suit. Ultimately, ownership dividends are a breath of fresh air in a market environment filled with speculation and the belief that stocks will only go higher forever, ignoring valuations and earnings in the process. Eventually, the craze for the most speculative stocks will break out, and the old Wall Street adage that stocks go up by escalator and go down by elevator will come true.

Dividends don’t lie

Intrinsic value is the “real” value of a stock, based on the dividends the stock is expected to pay over its remaining life. ——Joel Tillinghast

Many people are critical of receiving dividends. They argue that stock buybacks are superior from a tax perspective, noting that if investors need income, they can simply sell their shares to create the income. The fact that this is seen as a compelling argument is the real problem with today’s market and the advice being given to investors. The idea that I have to eliminate my ownership interest in order to create “income” is ridiculous.

This raises the real problem posed by share buybacks and illustrates why share buybacks are indeed inferior to dividends. A company’s owners receive real tangible benefits when a company makes profits and takes a portion of those profits and returns them to the business owners in the form of dividends. These profits can be used as income for retirees and other income-based investors, or the profits can be reinvested in more shares of the company. But dividends don’t lie. Either the company has earnings to distribute to shareholders, or it doesn’t. Dividends, and specifically dividend growth, are specific measures of a company’s business that show it is growing and well managed. Companies cannot fake dividends.

On the other hand, stock buybacks can be used by management as a tool to manipulate earnings through financial engineering. Many people will say, “As long as the stock price goes up, who cares?” But I disagree, paying the owners a portion of the profits and increasing the amount of profits paid to the owners each year, versus just buying back the stock, reducing the number of shares outstanding, thereby There is a very real difference between increasing gross earnings and decreasing earnings per share.

As the great accounting professor Abraham Brilloff described in his timeless book, Irresponsible Accounting, there are all kinds of games that companies can play. As the rules change, others have recently written books showing how companies manipulate their earnings in ways that only a trained eye can spot.

Dividends really don’t lie, and anyone who thinks dividends are irrelevant or unimportant is ignoring a wealth of evidence to the contrary. Perhaps, we need to question and revisit academic finance arguments written over 60 years ago, because clearly, they have not served us well.

The history of this thought away from dividends is well known. In fact, it’s so well known that I believe many investors simply quote the founding document (1961) without actually reading it…the document deserves careful review. A small percentage of them are still relevant. Unfortunately, the rest is so outdated that it’s now held to the wrong standard. ——Daniel Perris, “Ownership Dividends”

This quote, of course, refers to the 1958 paper by Modigliani and Miller, who made the argument that it did not matter how the balance sheet was financed and that companies should be valued solely on the basis of their assets and earnings potential. They expanded on this idea in their 1961 Business Journal article, “Dividend Policy, Growth, and Stock Valuation,” focusing on capital allocation.

In that article, they asked, “Is there an optimal payout ratio or range of ratios that maximizes a stock’s current value?” To answer this question, they relied on the academic theory of rational actors and perfect markets, stating: “The higher the dividend payments in any period, the more new capital must be raised from external sources to maintain any required level of investment.”

In response, Daniel Peris responded to academia in a 2018 critique of academic finance:

“Eighty years after the dramatic event (the 1929 crash), 75 years after the first analytical work (Graham and Dodd, Keynes, Williams), the first meaningful proposal for progress (Markowitz ) occurred 60 years after the critical simplification and extension of Markowitz’s ideas (Sharpe and Traynor), 50 years after the widespread implementation of MPT in bank trust departments, 40 years after Morningstar introduced the retail-style box and the move away from “doing ” The obvious shift to “doing” has been over 20 years ago. – Your own portfolio to a highly constructed model designed to generate maximum returns for a given amount of risk – After all these developments, in your best Clint Eastwood voice, you just have to ask yourself one question : Does it work? Well, did you do it? Does the system smooth investors’ returns, protecting them from downside, maximizing returns for a given level of risk, or vice versa? Does it create certainty where there is uncertainty? Judging from investor returns, the answer is no. Judging by the past two decades of stock markets—tech bubbles, then crashes, financial asset bubbles, then crashes, QE bubbles, then who knows what happens—the answer is no. Judging from the public’s view of the core system of Western capitalism, the answer is no! “

Dividend stocks outperform the market

erythrocyte

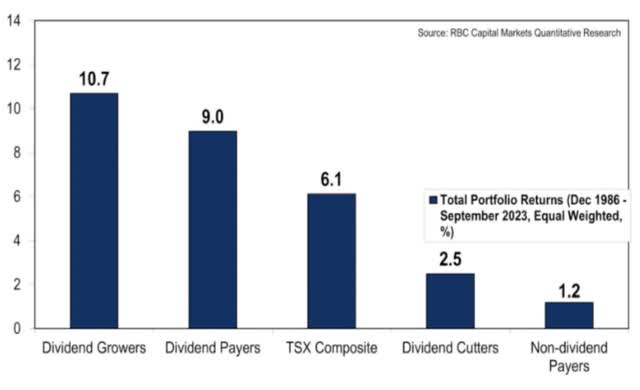

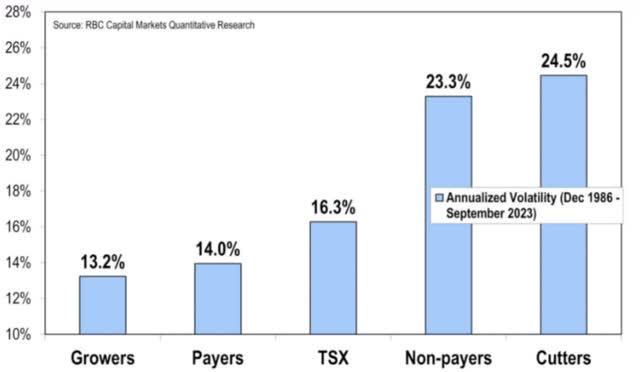

An analysis by Royal Bank of Canada shows that stocks of dividend payers and dividend growers generate the highest returns but also have the lowest volatility. Conversely, stocks that pay no dividends or cut their dividends generate the lowest total returns and the highest volatility. This data goes directly against the total return camp, which considers investing in these stocks to be “sub-optimal.”

Quantitative study of red blood cells

It’s no coincidence that many of the people who claim that dividend investing is inferior to total return investing are also factor investors. Factor investing is actually a nebulous field that was not practiced in the real world at the time the original academic work was created. I’ve laid out a lot of this in my articles on factor investing, which you can see here and here , so I won’t reiterate those arguments here. It’s clear from the evidence that dividend-paying stocks outperform non-dividend-paying stocks, and whether investors are pursuing income or investing for long-term growth, dividends account for the majority of total returns from equity securities.

in conclusion

Taken together, the arguments presented by Perris in his new book on dividends are an important starting point for discussions about the importance of dividends. They are a spark of hope to see markets return to investment value principles and move away from the speculative markets we have seen over the past 15 years. Ultimately, true investors must adhere to the radical idea that we are owners of businesses and that these businesses should pay us a portion of their profits in the form of dividends. We may be in the minority in this speculative market, but in the end, as the saying goes, slow and steady wins the race. I urge everyone to get a copy of “Ownership Dividends,” it’s one of the best books on investing and markets I’ve read in a while. In my next article, I will further explore academic finance and its criticisms of dividends, and further demonstrate that dividends are important to investors in the long run.