Tumor 3123

Author: Saskia Kot-Cheek and Marcus Schneider

Understanding the social risks posed by climate change requires discipline, nuance, and a systems approach.

The concept of “just transition” has gained popularity among responsible investors who are worried about the economic consequences of social transformation. The risks countries face in switching from fossil fuels to alternative energy sources. These risks are particularly high in emerging markets (EM). How do investors systematically measure them?

In short, a just transition requires transitioning away from fossil fuels in a way that takes into account the economic impacts without disrupting the social fabric of the economy.

For coal or oil exporting countries, especially those with relatively single economies, mismanaging the transition can have serious consequences. As demand for these goods declines, these countries may face more significant transition risks.The government may face fiscal and debt challenges, putting pressure on its sovereign credit Rating. Worse, economic deprivation and civil strife can lead to political instability and even regime change.

In developing a systematic approach to assessing these risks, it helps to focus on the sector at the heart of most transition strategies: energy production, especially coal (the most carbon-intensive fossil fuel). This has the added advantage that the coal transitions already underway in countries such as Germany, Poland, the UK and the US provide examples of policy lessons and pitfalls to avoid. These can be useful lenses for analyzing how emerging markets manage their just transitions.

Policy Lessons: Learning from Experience

For example, policy experience demonstrates the need for comprehensive, comprehensive government planning processes that focus on worker welfare, economic diversification, and social and environmental protection. A just transition cannot succeed without the help and commitment of national and local governments.

Planning is important, but the reality is that macroeconomic prerequisites such as existing levels of industrialization and infrastructure are critical to the government’s efforts to diversify coal-producing regions. Furthermore, existing labor market protections and social security networks are crucial to protect workers in their transition to alternative employment. The location of coal mines is also important in this case, as diversification in very remote areas (where many emerging market mines are located) is difficult.

Relative transition risks versus specific vulnerabilities

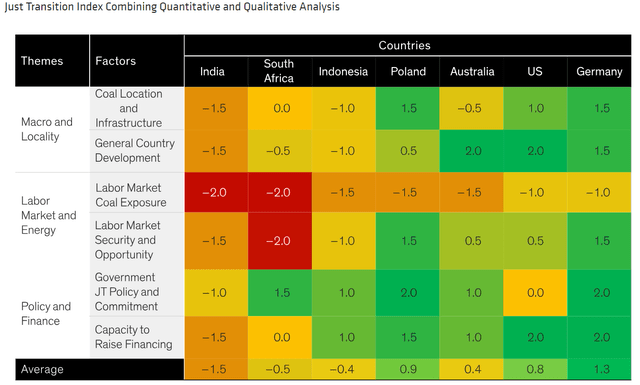

Based on past policy lessons, we created the Just Transition Index (JTI), which scores countries on a range of key indicators. The scores are designed to reflect a country’s overall level of macroeconomic development, the location of its mines, the composition of its labor and energy markets, the government’s policy commitment to a just transition, and its financing capacity.

Some indicators are relatively easy to quantify (such as a country’s level of development, its labor market’s dependence on coal, and its government’s budget capacity), while others (such as the location of coal mines and government reform commitments) are harder to quantify.

Therefore, we chose a qualitative index to score each country from -2 to 2, with the lowest number representing the greatest risk (exhibit). The JTI provides guidance not only on countries’ overall relative risks (contained in their average scores), but also on specific vulnerabilities (individual factor scores).

Coal transition risks facing the country: heat map

For illustrative purposes only. Current analysis is not a guarantee of future results. Not all countries are shown. As of February 28, 2024 (Source: AllianceBernstein (AB))

But the value of this approach to investors goes beyond its systematic nature. Basic qualitative research is critical to understanding the nuances of transition risk.

The precondition is a key variable

As mentioned earlier, emerging markets are particularly vulnerable. For example, labor rights and opportunities in emerging markets tend to be less extensive than in developed countries. In India, Indonesia and China, coal production is located far away from urban centers, limiting the scope for coal-dependent populations to obtain alternative employment without incurring relocation costs and disruption.

Poland illustrates this point well. The country’s transition away from coal began more than three decades ago.While the transition wasn’t seamless, it worked well in one major way: many Polish coal mining areas yes Work co-located with key industriessuch as automobile manufacturers and information and communications technology service providers.

The situation in Indonesia is different.Coal production is Mainly concentrated in Kalimantan and South Sumatra Accounting for 35% of East Kalimantan’s GDP. These areas are far away from the islands of Java and Bali, which together account for 60% of Indonesia’s population and GDP. But this challenge may be alleviated through plans to move Indonesia’s capital, currently Jakarta on Java’s northwest coast, to East Kalimantan.

A practical and potentially rewarding approach

Other policy lessons reflected in these examples are that stakeholder expectations should be managed (as Poland has shown, transformation can take decades) and that strategies should be holistic rather than piecemeal. (In Poland’s case, EU funding and other aid have helped coordinate the restructuring of the mining industry with the creation of new jobs.)

In emerging markets and elsewhere, just transition is a large, complex and long-term challenge. A systematic approach backed by solid fundamental qualitative research offers investors a practical and potentially rewarding way to participate.

The authors would like to thank ESG analyst Roxanne Low and fixed income associate Kristian Tonev of AB’s responsible investment team for their research contributions.

The views expressed in this article do not constitute research, investment advice or trading recommendations, and do not necessarily represent the views of all AB Portfolio Management teams. Opinions may change over time.

Editor’s note: Summary highlights of this article were selected by Seeking Alpha editors.